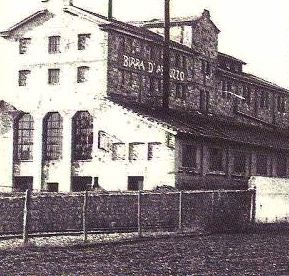

C’era una volta la Birra d’Abruzzo. C’era perché era il 1921 quando in un minuscolo paesino del Sangro nacque un birrificio che nel giro di pochi anni passò da una produzione di circa 2.000 ettolitri di birra a 6.000 e oltre. Una volta, perché quelle cifre diedero molta preoccupazione a qualcuno e, così misteriosamente come era esplosa, la Birra d’Abruzzo scomparve: passarono circa 9 anni, era il 1930 quando la Società Birra Peroni ne divenne azionista di maggioranza e nel 1936 lo stabile venne venduto, dismesso, la storia seppellita negli archivi napoletani dell’altra birra, la bionda che non voleva avversarie.

Per ricostruire le tappe e il valore della prima birra industriale d’Abruzzo e di una delle prime birre d’Italia è stato necessario andare a Castel di Sangro, dove si trovano tutti i documenti relativi a vita, miracoli e morte della Società Anonima Birra d’Abruzzo, creata nel 1921 a Montenero Val Cocchiara, uno scampolo di paese sospeso oggi tra Abruzzo e Molise, ma con sede amministrativa a Milano.

Si trovano lì perché quella storia è entrata nel cuore e nella vita di attento ricercatore di Maria Santucci, che gestisce la biblioteca comunale del centro sangrino: lei scoprì che a pochi chilometri dal posto dove viveva un tempo c’era stato un birrificio importante, perché il prodotto era tanto buono da conquistare i palati più attenti di tutta Italia; popolare, perché era distribuita capillarmente in città, borghi e villaggi d’Abruzzo, anche i più sperduti e in altre regioni d’Italia perché accanto alla fabbrica era nata la ferrovia; sostenibile, perché alimentata da una torbiera che dava materia alla fabbrica e lavoro a uomini, donne e giovani del posto, oltre 100, le cui vite professionali erano state meticolosamente annotate nei registri della società.

Scorrere il fascicolo è emozionante. Incredibile: una birra abruzzese negli anni ’20! Leggere che era diventata tanto potente da spaventare il colosso Peroni provoca orgoglio misto a rabbia, perché per via della qualità che faceva paura, quella birra scomparve e nessuno la reclamò, tranne la memoria che a circa un secolo di distanza l’ha ritirata fuori dal calderone dei ricordi, perché oggi in

Scorrere il fascicolo è emozionante. Incredibile: una birra abruzzese negli anni ’20! Leggere che era diventata tanto potente da spaventare il colosso Peroni provoca orgoglio misto a rabbia, perché per via della qualità che faceva paura, quella birra scomparve e nessuno la reclamò, tranne la memoria che a circa un secolo di distanza l’ha ritirata fuori dal calderone dei ricordi, perché oggi in  Italia e in Abruzzo la birra è tornata a contare qualcosa, grazie alla fioritura di ottimi birrifici artigianali.

Italia e in Abruzzo la birra è tornata a contare qualcosa, grazie alla fioritura di ottimi birrifici artigianali.

La storia di quella birra è rilegata in un raccoglitore conservato in una stanza ampia e luminosa della biblioteca dove incontriamo Maria. Di quella biblioteca lei è l’anima, ma anche di un po’ di vita culturale del posto, a cui contribuisce organizzando eventi, incontri di filosofia, poesia e dove ha portato anche quella storia, ad un Festival della birra del 2003, con la testimonianza diretta raccolta da un lavoratore, contenuta in un libricino che ha fatto strabuzzare gli occhi a quanti non sapevano cosa ci fosse mai stato dentro a quell’edificio abbandonato vicino alla stazione.

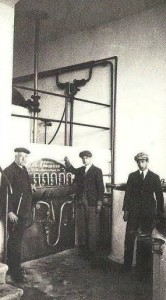

Lo stabilimento ieri

Lo stabilimento oggi

Maria Santucci

“Il birrificio è nato al posto della torbiera – racconta – che dava lavoro e combustibile al comprensorio di Castel di Sangro, Villa Scontrone, Scontrone, Montenero e forse anche Rionero. Estraevano la torba con le vanghe, da un terreno ricchissimo di acqua e la portavano allo stabilimento con dei carretti a binario per lavorarla. Durò finché non arrivò il carbone tedesco e quella torbiera diventò antieconomica. E fu così che il combustibile andò ad animare la produzione di birra che fece tornare a nuova vita lo stabilimento e i suoi lavoratori. Era il 1920/21”. In quegli anni l’Italia ricominciò a produrre birra. I birrifici nacquero nel nord, nel 1890 c’erano 140 fabrichette in tutto lo stivale. Nel ‘900 scesero a 99, e quando la Birra d’Abruzzo cominciò il suo viaggio erano 58 in tutto. Maria ha attinto notizie dalla testimonianza di Nicola Buzzelli, uno di quei lavoratori che costruirono questa storia, classe 1900, all’epoca aveva 20 anni.

Perché le ha cercate? Sorride e mite dice: “Perché è un pezzo della storia di questo territorio, così straordinario che non poteva andare perduto”. Per riaverlo ha chiesto le carte degli inventari Peroni conservati all’Archivio di Stato di Napoli e quando li scorre si stupisce della modernità di quell’impianto, concepito per dare benefici a tutta la Piana e anche oltre: “Per la stazione di Montenero significò vita – spulcia i documenti per dimostrarlo – perché arrivava materiale e dovettero fare scambi, persino un ponte a bilico di 30 tonnellate inserito nel raccordo che c’era dentro lo stabilimento. Qui ci sono le richieste degli amministratori di allora, accordate dalle Ferrovie dello Stato, lungo quei binari correva il traffico di luppoli dalla Germania, casse di orzo caramellato, di bottiglie, di lieviti e a mano a mano che queste merci arrivavano la produzione della birra saliva, lo stabilimento andava a gonfie vele”.

Perché le ha cercate? Sorride e mite dice: “Perché è un pezzo della storia di questo territorio, così straordinario che non poteva andare perduto”. Per riaverlo ha chiesto le carte degli inventari Peroni conservati all’Archivio di Stato di Napoli e quando li scorre si stupisce della modernità di quell’impianto, concepito per dare benefici a tutta la Piana e anche oltre: “Per la stazione di Montenero significò vita – spulcia i documenti per dimostrarlo – perché arrivava materiale e dovettero fare scambi, persino un ponte a bilico di 30 tonnellate inserito nel raccordo che c’era dentro lo stabilimento. Qui ci sono le richieste degli amministratori di allora, accordate dalle Ferrovie dello Stato, lungo quei binari correva il traffico di luppoli dalla Germania, casse di orzo caramellato, di bottiglie, di lieviti e a mano a mano che queste merci arrivavano la produzione della birra saliva, lo stabilimento andava a gonfie vele”.

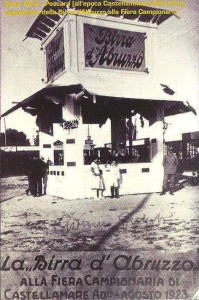

Dai report dei distributori si leggono gli elenchi di decine e decine di paesi e paesini della provincia di Chieti, Teramo, L’Aquila, Pescara. La Birra d’Abruzzo fu madrina persino della Fiera Campionaria di Castellammare Adriatico nell’agosto del 1923 per quanto era diventata popolare. “Era buona perché sostenibile – “sostiene” la nostra bibliotecaria, rimarcando l’attenzione su un ingrediente non trascurabile – per via dell’acqua. Un’ottima acqua di cui il territorio era naturalmente ricco, che con l’aumentare della produzione richiese l o scavo di un pozzo ad hoc per la fabbrica. Queste componenti e un ottimo ambiente di lavoro furono il segreto che rese la Birra d’Abruzzo competitiva e fece spaventare le altre etichette: si bevve di più della nota Birra Meridionale e poi, con il suo prezzo di 2,30 lire, attaccò di petto la birra delle birre di quegli anni, la Peroni”. E’ storia, ad esempio, che l’allora rappresentante Peroni, tal Filippo Murolo, vide calare il numero dei carri di birra Peroni in loco da 70/80 l’anno a 2 o 3 in tutto, perché la gente preferiva la birra “locale” e non solo in Abruzzo, perché quella birra arrivò anche a Milano e allo stesso prezzo. Non servì a nulla portare il prezzo della prima a 2 lire, nella Piana si continuava a bere abruzzese, perché lo

o scavo di un pozzo ad hoc per la fabbrica. Queste componenti e un ottimo ambiente di lavoro furono il segreto che rese la Birra d’Abruzzo competitiva e fece spaventare le altre etichette: si bevve di più della nota Birra Meridionale e poi, con il suo prezzo di 2,30 lire, attaccò di petto la birra delle birre di quegli anni, la Peroni”. E’ storia, ad esempio, che l’allora rappresentante Peroni, tal Filippo Murolo, vide calare il numero dei carri di birra Peroni in loco da 70/80 l’anno a 2 o 3 in tutto, perché la gente preferiva la birra “locale” e non solo in Abruzzo, perché quella birra arrivò anche a Milano e allo stesso prezzo. Non servì a nulla portare il prezzo della prima a 2 lire, nella Piana si continuava a bere abruzzese, perché lo  stabilimento nel frattempo era diventato luogo di incontro e socializzazione. Tanto che chi vi passava per caso e si intratteneva con gli operai riceveva da questi una bottiglia da portarsi via gratis e spesso tornava a casa con una cassetta da 25, per quanto aveva gradito la politica di marketing territoriale nato insieme a quella birra! Così si legge nel racconto dell’operaio.

stabilimento nel frattempo era diventato luogo di incontro e socializzazione. Tanto che chi vi passava per caso e si intratteneva con gli operai riceveva da questi una bottiglia da portarsi via gratis e spesso tornava a casa con una cassetta da 25, per quanto aveva gradito la politica di marketing territoriale nato insieme a quella birra! Così si legge nel racconto dell’operaio.

“Dava benessere al territorio, era un prodotto amato – continua Maria – e chi lo faceva ne era primo promotore perché sapeva con che cosa era fatto. Anche i resti degli ingredienti tornavano al territorio: l’orzo caramellato, ad esempio, non veniva buttato via, ma rivenduto a poco agli allevatori del posto per alimentare mandrie e bestie varie. E’  stupefacente scoprire dal fatturato i miracoli di questo birrificio, sempre in attivo, toccando punte milionarie e una produzione in continua crescita, tanto che anche quando vennero messe delle imbottigliatrici automatiche la richiesta era sempre maggiore del prodotto, finché la Peroni non cominciò a farsi avanti per acquistarla. Dalle carte si può solo desumere cosa accadde, perché la fabbrica fu venduta, cosa, forse, convinse gli azionisti a cedere le quote nel momento di maggiore splendore economico dell’impresa. Nero su bianco ci fu una convenzione, in virtù di cui la Peroni si impegnava a tenere aperto lo stabilimento, ma per la sua etichetta. Ma così accadde per pochi anni, quelli prima dell’epilogo”.

stupefacente scoprire dal fatturato i miracoli di questo birrificio, sempre in attivo, toccando punte milionarie e una produzione in continua crescita, tanto che anche quando vennero messe delle imbottigliatrici automatiche la richiesta era sempre maggiore del prodotto, finché la Peroni non cominciò a farsi avanti per acquistarla. Dalle carte si può solo desumere cosa accadde, perché la fabbrica fu venduta, cosa, forse, convinse gli azionisti a cedere le quote nel momento di maggiore splendore economico dell’impresa. Nero su bianco ci fu una convenzione, in virtù di cui la Peroni si impegnava a tenere aperto lo stabilimento, ma per la sua etichetta. Ma così accadde per pochi anni, quelli prima dell’epilogo”.

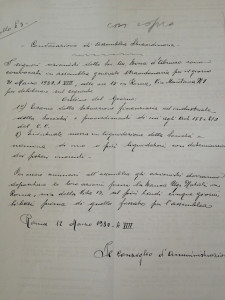

Siamo al ’36, il 21 marzo, quando venne convocato un consiglio di amministrazione in cui si decise la fine di quell’avventura. Uno dei sindaci, il liquidatore, si dimise e dopo l’avvocato Luigi Lepore gli altri sindaci cedettero le loro quote ricevendo le liquidazioni. Nel verbale di quell’assemblea venne aggiunto lo stato patrimoniale della società, le proprietà, la produzione, così gli anni di lavoro e conquista di un mercato prima inesistente furono trasformati in semplici cifre. L’atto notarile seguito a quell’assemblea porta la data del 19 settembre 1936 e sancì chiusura e vendita all’asta di edificio e i macchinari, le attrezzature vennero smontate e disseminate nei magazzini del miglior offerente.

Siamo al ’36, il 21 marzo, quando venne convocato un consiglio di amministrazione in cui si decise la fine di quell’avventura. Uno dei sindaci, il liquidatore, si dimise e dopo l’avvocato Luigi Lepore gli altri sindaci cedettero le loro quote ricevendo le liquidazioni. Nel verbale di quell’assemblea venne aggiunto lo stato patrimoniale della società, le proprietà, la produzione, così gli anni di lavoro e conquista di un mercato prima inesistente furono trasformati in semplici cifre. L’atto notarile seguito a quell’assemblea porta la data del 19 settembre 1936 e sancì chiusura e vendita all’asta di edificio e i macchinari, le attrezzature vennero smontate e disseminate nei magazzini del miglior offerente.

La Birra d’Abruzzo divenne un ricordo senza lieto fine, per quelli che la bevvero e per quanti la produssero. Nessuno seppe mai il perché di quella scelta, è che di fronte alle vicende umane complesse la realtà si arrende a spiegazioni semplici. Così la logica del pesce grande che vinse sul pesce piccolo rese “accettabile” quella perdita, plausibile.

“Eppure quella birra ha dimostrato quanto il territorio poteva diventare forte con gli ingredienti giusti – conclude Maria la bibliotecaria – Se l’entusiasmo degli inizi fosse rimasto, non si fosse corrotto, forse ora avremmo una birra nota in tutto il mondo, come l’altra. Le premesse c’erano tutte, le basi erano buone, quell’esperienza fu antesignana, anche di una produzione rispettosa dell’ambiente, che prendeva dal territorio e al territorio restituiva sia i materiali sfruttati, come fertilizzanti e cibo, sia il prodotto a prezzi accessibili a tutti. Una storia unica, per quei tempi e anche per quelli contemporanei”.

“Eppure quella birra ha dimostrato quanto il territorio poteva diventare forte con gli ingredienti giusti – conclude Maria la bibliotecaria – Se l’entusiasmo degli inizi fosse rimasto, non si fosse corrotto, forse ora avremmo una birra nota in tutto il mondo, come l’altra. Le premesse c’erano tutte, le basi erano buone, quell’esperienza fu antesignana, anche di una produzione rispettosa dell’ambiente, che prendeva dal territorio e al territorio restituiva sia i materiali sfruttati, come fertilizzanti e cibo, sia il prodotto a prezzi accessibili a tutti. Una storia unica, per quei tempi e anche per quelli contemporanei”.

Già e oggi, a 92 anni di distanza, non dovremmo combattere con l’orgoglioso ricordo della Birra d’Abruzzo che la Peroni dovette acquistare perché era troppo buona per accettare di mettersi in competizione. (al termine della traduzione la foto gallery).

[divider]

The sad, beautiful tale of Birra d’Abruzzo: Italian excellence since 1921.

Once upon a time there was… Birra d’Abruzzo (1). Once upon a time there was a brewery, built in a small village near the Sangro river; it was 1921. In a few years’ time, the amount of its production grew from 2000 hLs to more than 6000 hLs, and someone started worrying about this. Therefore, as mysteriously as it arrived, Birra d’Abruzzo disappeared: in 1930, nine years after its foundation, the Peroni Company became its majority stakeholder and in 1936 the building was sold, disused, abandoned. The Birra d’Abruzzo history was buried forever in the local archives of the Naples headquarters of its rival who was willing to reign as “the unrivalled ale beer”.

But now, let’s unearth the stages and the values lying behind the history of the first manufactured beer from Abruzzo, one of the first Italian-brewed beers. In order to do this, we must start our journey from Castel di Sangro, where you can find all the documents about the life, the death and all you need to know about the Società Anonima Birra d’Abruzzo, founded in 1921 in Montenero Val Cocchiara, a remote village between Abruzzo and Molise, with its headquarters in Milan.

All the documents are there because the history of Birra d’Abruzzo entered the heart and life of Maria Santucci, a scrupulous researcher managing the municipal library of Castel di Sangro, after she found out that, just few kilometers away from the city she lived in, a brewery had been there for a while. It was “an important one”: its product was so delicious that seduced the finest tastes of Italy; it was “a popular one”: the widespread distribution system of the product among cities, boroughs, villages, among the remotest places all over Abruzzo and many other Italian regions was made possible by its proximity to the railway; it was “sustainable”: it worked thanks to a peatland; peat provided both energy to the factory and job to more than 100 men, women and young people, local citizens whose work histories were meticulously registered among the Company files. Browsing those documents is an exciting experience. That was amazing: a beer in Abruzzo in the twenties! When we read about the outstanding power acquired by the Company (so much outstanding that, as a performance powerhouse, the Peroni Company started worrying about it), the feeling we get is a mixture of pride and anger: its high quality was worrying, and this was the cause of its extinction. Besides the recollection of it, no one wanted it back. Today, in Italy, and here, in Abruzzo, thanks to the flourishing of excellent craft breweries, beer matters, again. That’s the reason why, almost a century after the foundation of Birra d’Abruzzo, we want to start a walk down the Memory Lane.

Its history rests in a folder, stored in an ample and bright room in the library where we have met Maria. She’s the soul that animates both that library and the cultural life of the village to which she contributes through the organization of several events and through philosophy and poetry meetups. Just during one of these activities (a 2003 Beer Festival) she decided to bring that history back thanks to the direct evidence of it provided by one of the workers of the brewery: the evidence had been jotted down in a small booklet so that everyone could realize what once went on inside that dismissed building near the railway: the eyes of those who didn’t know anything about that were wide with amazement.

“The brewery replaced the peatland”-she says- “it once provided fuel and job to the district of Castel di Sangro, Villa Scontrone, Scontrone, Montenero and-maybe- Rionero. Peat was extracted by lifting spades from a high water table and was carried by rail track trolleys to the factory, where it was converted into energy. This situation lasted until the coal started arriving from Germany, thus making the costs of the peatland too high. Thanks to the coal, the beer production was the starting point from which the brewery and its workers came to new life. It was 1920/1921”. Those were the years in which Italy started brewing beer, again. At the beginning, breweries were mainly founded in the North of Italy, and in 1890 the amount of breweries all over the country was close to 140, but in 1900s it was reduced to 99. When Birra d’Abruzzo first appeared, there were only 58 of them. Maria obtained these pieces of information thanks to the evidences given by Nicola Buzzelli, born in 1990, one of those workers that let this story come true. At that time, he was 20 years old.

But why did she gather these pieces of information? In hearing this question, she smiles, and, balmly, says: “Because it’s a piece of history of this land, and it was so outstanding that it definitely should not be lost.” She gathered them from the inventory of the Peroni Company, stored in the Naples State Archives. Just briefly looking at those pieces of information, she feels astonished by the advanced technology of the plant, conceived to give benefits to the whole district and beyond. “That meant ‘a new life’ for the railway station in Montenero- and she goes through the documents to prove it. Material was brought there, exchanges used to take place there and a 30 Tons. bascule bridge was built into the plant. And here, look, here are the application form from the then directors, allowed by Ferrovie dello Stato. Hops from Germany, boxes full of caramelized barley malt, glass bottles and yeasts used to run along those railways. The more products were imported, the highest amount of beer was produced: the brewery was going extremely well”.

Among the accounts of the distributors we find a list including dozens of towns and villages in the province of Chieti, Teramo, L’Aquila and Pescara. Thanks to its popularity, Birra d’Abruzzo had a major role in the August 1923 Trade Fair in Castellammare Adriatico. “It was a good beer, as it was sustainable thanks to the water” says our librarian Maria, underlying the fundamental importance of this ingredient. “Even though the soil was naturally rich of high-quality water the growing amount of beer production was the reason for a special water well to be built. All those elements, together with a positive working environment, were the main ingredients of the Birra d’Abruzzo to become such a competitive product that it started daunting the other brands: it became the best-selling beer (more than the famous Birra Meridionale), and, thanks to its competitive price (2.30 lires per bottle (2)), managed to challenge “Peroni”, one of the best rated beer until that time. Moreover, the decreasing amount (from 70/80 per year to 2/3) of local Peroni beer wagons experienced by the then representative of the Peroni brewery is already a historical landmark: it was clear that local people preferred craft beer, the same beer that started arriving in Milan , too, at the same price. The decision of Peroni beer to lower the price to 2 lires per bottle was made in vain, as people kept on drinking beer from Abruzzo when the plant turned into the perfect gathering place for social interactions. In fact, those who happened along the plant and engaged in conversation with the workers usually got from them an extra free bottle. Moreover, the territorial marketing strategy born together with Birra d’Abruzzo was so appealing to them that they often came back home with a 25 bottles box. This is what we read in the account of that worker.

“That beer was beneficial for the area, and it was loved”- continues Maria- “those who produced it were the first to love it and to promote it, just because they were aware of what that beer was made of. Leftover ingredients coming from the land used to return to the land itself: for example, caramelized barley malt was not just thrown away, it was sold at a low price to local farmers and used as animal feed.

It is astonishing to learn about the “miracles” around this brewery: firstly, thanks to its unceasingly growing production, its turnover approached almost one million lire; secondly, even if some automatic bottlers were introduced, thus fastening the production itself, the demand was constantly higher than the quantity actually supplied. This lasted until Peroni Company acquired it. That’s what we can infer from the documents of the Company: the plant was sold, and that was enough for the shareholders to dispose of their shares during the most favorable period of the Company. An agreement was put on paper, according to which the Peroni Company committed itself to keep the business running under its own brand. This situation went on for few years, the same years before the end of everything”.

In March 21st 1936, a meeting of the Board of Directors decided to put an end to all this. One of the Auditor, Luigi Lepore -the liquidator- decided to resign; the other Auditors soon followed, selling their shares and receiving their proceeds. The Minutes kept during that meeting recorded the balance sheet of the Company, its properties and production: the years spent on working hard to make the brewery stand out and shine in this as-yet unborn market were now just numbers. The notary deed following that meeting, dated September 19th, 1936, enacted the closing of the business, and an auction sale was set up so that the building and the machineries could be sold. The equipments were dismantled and distributed among the higher bidders’ wharehouses.

Birra d’Abruzzo is a memory with no happy ending both for those who had the chance to drink it and those who produced it, but nobody has ever been able to fully understand the reasons behind that choice. When dealing with human complex situations, it is clear that truth is usually replaced by a simpler interpretation: the “bigger fish eats the little ones” explanation was what made that loss acceptable and reasonable.

“Nevertheless, that beer showed how much the region could have become powerful just with the help of the right ingredients”-Maria concludes- “if only the eagerness of the first period had remained, and if it hadn’t been corrupted, we would have had one of the most popular beer in the world: Birra d’Abruzzo had a favorable background and good starting points to become as famous as its rival Peroni, as it already was a forerunner of sustainable production: it took resources from the land, but it also gave them back both in the shape of recycled materials, such as fertilizers and food, and in the shape of a product with an affordable price for everyone, as well. It’s been a unique story for that period (and for the contemporary one)”.

Now, 92 years later, we wouldn’t have had to deal merely with the proud memory of Birra d’Abruzzo, if only the Peroni Company hadn’t bought it: the only fault of Birra d’Abruzzo was just the fact that it was so good that its rival chose not to compete against it.

(traduzione di Valentina Marinelli)

(1) The name of a beer once brewed in Abruzzo, a region in the centre of Italy.

(2) “Lira”: the official italian currency before euro.

E’ una storia stupenda ma anche molto triste. Ci facciamo sempre schiacciare da chi è più forte invece di combattere con i denti e a tutti i costi per i nostri sogni che poi sono invece delle splendide realtà.

sarebbe bello rilanciare il progetto e trovare la ricetta originale …

Complimenti alla splendida donna, bibliotecaria, custode e non solo della memoria collettiva per averci fatto conoscere un pezzo di storia. Poi sono d’accordo con Luca, perchè non rilanciare il progetto? Birra artigianale e ecosostenibile…sarebbe una bella avventura!

Teresa

Complimenti per il bel articolo anche se devo dire che, lascia un po di amaro in bocca.

ecco a cosa serve conservare le famose ‘vecchie carte”.

bravi gli archivisti !

Non avevo idea che ci fosse una stata una realta’ del genere nel cuore del nostro Abruzzo!Bravi gli archivisti e bravi coloro che vogliono riportare alla luce con orgoglio questa che probabilmente e’ solo una delle storie industriali del nostro Abruzzo.Guardandoci intorno quando si attraversa il nostro territorio si scorgono qua e la’ edifici decadenti di antica origine produttiva.Spero che altri amministratori abbiano questa stessa volonta’.

Signora Santucci, buongiorno. Ci conoscemmo di persona alla presentazione del noto romanzo storico, al museo di Alfedena, lo scorso agosto 2013. Mi complimento con voi per l’ottima ricerca e documentazione della nostra cara birra del Sud, scomparsa a seguito delle note vicende economico-egemoniche nel 1936, quando il baricentro dell’economia italiana si andava affermando vieppiù al Nord. Conoscendo la vostra passione per la cultura del nostro territorio, per il fascino ancestrale delle nostre montagne, delle nostre radici, le mie congratulazioni vi giungano fervide. La malinconia che può suscitare tale storia non deve pregiudicare il futuro. La vocazione industriale in ambito agro-alimentare abruzzese-molisana va rilanciata, puntando sul modello cooperativo. Non possiamo che auspicare l’iniziativa e buona volontà dei giovani. Abbiatemi con vivissima cordialità. Prof. Fernando Crociani Baglioni . Alfedena-Roma.